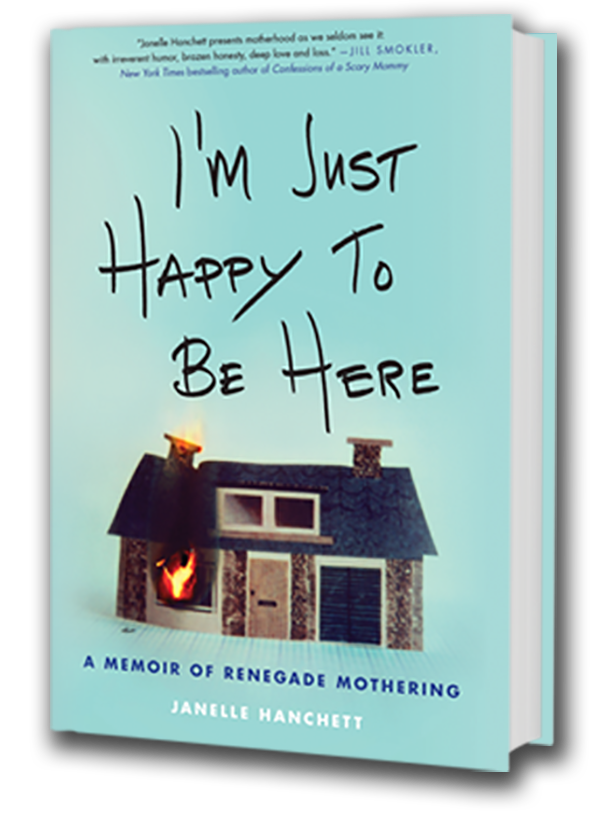

Friends, I am really excited to share this excerpt from Chapter 1 of my book, I’M JUST HAPPY TO BE HERE, which is out in EIGHT DAYS, on May 1.

I cannot wait for you to read this.

And hey! I’m coming to a few cities. Check them out, and come say hello if you can. I’d love to meet you.

Anyway, here we go. Eight days. What a life this is.

From Chapter 1: Family Planning on Ecstasy

The first thing I did when I found out I was pregnant with my first child was head out to the balcony of our one-bedroom apartment and smoke a cigarette. It wasn’t even a real balcony. It was a gray stoop barely big enough for one unwatered plant, a dusty mat, and a twenty-one-year-old in vague denial. I would have preferred outright denial but found it impossible, having just peed on two sticks offering no ambiguity.

My plan was to formulate a plan out there on the balcony before informing the father, who was my boyfriend of three full months. We shared the apartment, but I made sure I was alone that afternoon, protected in isolation, so nobody would see me cry, or rage, or decide to handle the situation silently. I was never the kind of person who wanted company in moments of vulnerability. I never wanted a concerned friend to pat my head and smooth the hair off my forehead while I puked or cried. I wanted to lie in bed in solitude, where I could turn my head to the wall, stretch my legs out, and rise again smiling, while the world slept soundly in its room.

The last thing I needed was a loving and emotional man celebrating the seed in my womb before I knew how I felt about it.

Moments before, I had stared at those double lines with detached curiosity, a sort of numbed awe, as they popped up without hesitation in what seemed like a “fuck you” pink. I figured there could still be some mistake, so I took another test, and upon the second neon positive, pulled up my jeans, walked through the living room and onto the balcony, grabbing my Camel Lights and lighter on the way. I allowed my condition to sink one inch into my brain, where it hovered like a storm cloud creeping toward me. I knew it would shower me in panic, and soon I would feel it pouring down my arms and into my shoes, but those first moments felt liminal, half-real. I emboldened them with a cigarette. One more cigarette in the line of a thousand before it, a meaningless action of my same old life. An action of the nonpregnant.

Nothing to see here, folks. Just another woman on a balcony having a smoke.

That February afternoon was cool and bright, and as I watched the cars do nothing in the parking lot of our apartment complex, I thought about being a senior in college, my job as a waitress, and the few months Mac and I had been together, most of it grayed and hazy from alcohol, fast and romantic and possibly fake. I thought about how he would respond if he were there.

He would smile a soft smile. “Wow,” he would say, “I love you so much,” and his eyes would fill with grateful tears as more supportive words crossed his lips. He would study my reaction with his huge brown eyes. He would look as if he had waited his whole life to hear those three words.

I am pregnant.

I took a drag, inhaling I could have an abortion, but exhaled the startling realization that I would not.

And with the thought, the cigarette grew foul between my fingers. I stamped it out beneath my foot and wondered how the fuck I had ended up here again. I understood the physiology of pregnancy. I did not understand how that wasn’t enough.

In my defense, the first one was an honest mistake. I was eighteen, in my first semester of college, and had spontaneous, unprotected make-up sex with my long-term boyfriend. I knew immediately I would not have that baby, and I did not feel guilty about that decision, though I suspected this made me something of a monster. I felt sadness, but at that age, in that life, I mostly felt relief. We had sex, and yes I happen to have a uterus and ovaries hell-bent on reproduction, and our act was neither smart nor mature, but it was his fault too. My defense was that of a petulant child, but I had no interest in spending my whole life paying for a five-minute interval of questionable sex with a man who could walk away if he felt like it.

As I stood on the balcony, I wondered again, Who the hell gets pregnant accidentallymore than once?

I stared at the horizon and shook my head in disgust as I traveled the recesses of my brain looking for answers, recalling only a woman in my freshman comparative literature class. She had told me, “Getting an abortion is like getting your teeth cleaned.” When I raised an eyebrow, she explained, “It’s just something you have to do.” She was in her thirties and married to a local rock star. She had bad teeth, three children, tattoos, and that haircut of the ’90s where bangs were cut stupidly short in a band right against the forehead. I respected her.

Her teeth cleaning theory sounded erroneous if not downright depraved, but her nonchalance convinced me I would be alright, and that I was even perhaps not quite as foul as I had believed during my trip to the clinic that week, feeling like a slut and regretting with my whole heart those minutes in the dorms.

Apparently this is a thing women do.

That seemed true. I did it.

But I would not do it now.

And it didn’t feel like the fucking dentist.

Back inside, I stretched out on our quilt-covered couch, clicking my tongue at Fatboy, the giant black-and-white cat we inherited from Mac’s childhood. When feeling particularly affectionate, Fatboy would turn his head and glance at you from across the room. But that day, he folded up in the crook of my knees and stared up at me, as if he knew things were heavy.

I took a deep breath, looking around the apartment, the carpet so bland I couldn’t tell what color it was, the kitchen and bathroom floors a yellowed linoleum with pastel blue squares, ripped up and black at the corners. The cabinets were a 1970s brown with gold handles, and metal mini-blinds hung above a box air conditioner in the window that would sputter along against California’s Central Valley heat. That summer, we moved our mattress beneath the little box, creating a pocket of decency between the white walls. Our television sat on boards and cinder blocks. It was the kind of apartment that never felt alive or permanent, but Mac and I were kids and in love, and it was ours.

He was nineteen and I was twenty-one.

I was right about Mac. He did smile through tears and say all the lovely things I suspected he’d say when I told him I was pregnant, but the next day he added, “If you don’t have our baby, I can’t stay with you.” I considered telling him about the moment I knew I wouldn’t have an abortion, but instead I merely nodded. I wasn’t ready to speak the words, “I am having a baby.” I was stretching the liminal gray a few days longer.

When he spoke those words, he didn’t read my face to adjust his tone. He was not afraid of my response, or conflict, and there was no subtext. It was merely data to inform a decision. If his statement had been a threat, an attempted entrapment, I would have left immediately on those grounds alone. Fuck you for even trying to get me to stay, I’d have thought.

But that’s not what he said, and I knew it, because he said it with warm acceptance in his eyes and mouth and forehead—the way he looked at me when he said everything, even when he yelled and postured and I thought maybe I hated him. Or, perhaps that’s why I hated him, because he seemed capable of only adoration, and even in his anger he was devoted and irrationally loyal. It made me feel a little sick.

I get it, man. You can’t withstand the resentment you’d feel toward me if I didn’t have our baby.

But he is not why I had her. I was always going to have her and I knew it, though I didn’t know how to explain that I knew. I didn’t understand yet that motherhood is a lot of knowing without knowing.

But I knew her. She was already made.

I was afraid of having a baby. I was afraid of committing to him like that. I was afraid of what my parents would say, but Mac misread this fear as indecision. I had her because she was meant to be here and I was meant to be her mother, and I believed that in the same way I know the sun will rise. I had her because the moment I knew of her, she existed, like a strange new friend who moved in and wouldn’t leave.

I told myself I was about to graduate from college, that I wasn’t that young, that Mac was going to be a good father—and I loved him, or thought I did. In this way, I rearranged the facts, the furniture of my life, to accommodate my new friend.

Two weeks later, Mac peeked his head over the curtain while I showered and said, “It’s going to be a girl.”

“I know,” I said, and laughed. How weird we are, I thought. Clairvoyant.So in love she’s already shining through—through the blood and walls of my body.

We thought of names. We thought of Aurora and Leah and Althea, but one day while I waited for customers to arrive for dinner in the restaurant where I waitressed, I flipped through a magazine and found an article about Ava Gardner.

We settled on Ava Grace, as if anything could be more beautiful.

I told my mother I knew she was a girl; she didn’t think that was strange at all. When I asked her what the hell I was going to do with my life now, she said, “Well, honey, you’re going to have a baby.” Her simplicity and perky use of the word “honey” shot red annoyance down my spine.

My mother’s perpetual optimism made me wonder if she existed in some sort of sociopathic love cloud. As a young girl, I joined in her optimism, jumped on the “it’s going to be great!” train with glee, but over the years, as each new beginning almost never turned out “great,” I realized her outlook was as much fantasy as it was hope. It was a story to justify rushing headlong into another disaster, the same thing we’d done for years. Businesses. Marriages. Personality improvements. Diets. It was always going to be different this time.

It was an old, raw burn, and her sweetness still stung.

The moment she mentioned relationships, mine or hers, somewhere in me the memory of my former stepfather stirred, the way we moved in and out of his house like a vacation rental. But mostly, I remembered her suffering and how I thought I could fix it, how the solution was perfectly clear to me, how everybody said I was “very mature for my age.” My mother used to say, “I don’t know how you see the things you see, Janelle.”

I didn’t either, but I wished she’d see them too, because I was tired. And even at twenty-one, I was still tired, perhaps more tired than I’d ever been, and I had long since stopped believing in her dreams.

And yet, I always called her first, to bathe in the optimism she turned toward me, too, toward the person she believed I could become. I needed that. I needed to believe things were going to be different right around the corner. That sick hope was infectious, seeping into me whether I wanted it or not, and as much as I distrusted it in her, I clung to it like a drowning woman, because at least it was something.

“But how do you know, Mom?” I didn’t mask my irritation.

“Because you are going to be fine, sweetie.” I wanted to throw up.

She must have told her mother right away, because the next day Grandma Joan called and said, “You know you don’t have to marry this guy just because you’re pregnant,” and my jaw hit my flip phone. I wasn’t anywhere near marrying Mac. I barely knew him. I am merely going to have his baby, Grandma.

Being a woman born in 1930, Grandma Joan of course assumed marriage, and I assumed she would push marriage. She was in her seventies and a Mormon woman who had made her husband dinner every night since they were married at eighteen, and if she was not home in the evening, she prepared the food and put it on the counter so all he had to do was heat it up. He had been the quarterback of the high school football team and she had been the new girl in town—and a cheerleader. It was a movie, and yet true. They still held hands when they sat on the couch together, and they flirted like teenagers. He was sure old Benny at the post office was waiting for him to “kick the bucket” so he could swoop in on Grandma.

She would smack his leg, roll her eyes, and say, “Oh, Bob,” with exasperation and a kiss in her eye.

At family functions in her home, all the women would bustle around the kitchen for hours preparing dinner for thirty while the kids played in the basement and the men watched football in the living room. After dinner, all the women would bustle around in the kitchen for hours doing dishes while the men watched football in the living room, and the kids ran around in the basement. By the time I was a teenager, I wondered what the hell was wrong with these people. But I loved being in the kitchen, where my mother and three aunts talked and cooked with the chatter and laughter of a lifetime of sisterhood, occasionally popping out to rescue a screaming baby, talking of report cards and breastfeeding and wayward teens, of Grandma’s silly ways and how she really should sit down, she’s tired, but she never would. When she finally did, my uncles had begun barbequing on the deck outside and nobody played in the basement anymore.

I sat with the men, too, as babies crawled around their laps, each of their faces illuminated with the television screen as they watched sports, speaking of things I didn’t understand, like “downs” and “bad calls” and “finals.” I felt honored when they spoke to me, a little nod to my sport-less existence. I understood their acknowledgment of me was a quick trip beneath themselves, a little jaunt to a place less sacred. They were, after all, the ones who got to do nothing while groups of women worked on their behalf.

Although the kitchen was warmer, and had better conversation, sometimes I would sit at the dining table between the living room and kitchen, so I could watch both ends and refuse to commit.

At twenty-one, I joined the women in the kitchen for good, though I had always promised I’d never be like them. “I’m not going to get married until I’m thirty,” I’d say as a teenager at our annual Christmas party, “and I won’t have a baby until thirty-five.”

“Good job,” my aunt would nod. “Just don’t rush it.”

“Of course not,” I’d answer, irritated that she’d even consider the possibility of me ruining my life with an unplanned pregnancy at a young age.

I was the youngest of my cousins to have a baby.

People surprise you, though, especially when they’re old and sick of the bullshit, and I saw Joan anew the day she called me, after fifty-five years spent with my grandfather. While she spoke, I wondered how many women of her generation married terrible men because of unexpected pregnancies, and then stayed because of more. I felt myself, for an instant, counted among them.

“Thank you for your concern, Grandma, but it’s different with us,” I said.

I may be in the kitchen like the rest of you broads, but I am different. I could not articulate how, exactly, but I knew I wouldn’t end up washing dishes while the men watched other men slam into each other on brightly lit screens. It seemed archaic and absurd. I would demand freedom, even within the confines of pregnancy. I suppose that, too, is something women “just have to do.”

If I had to guess, I would have said my future would unfold more along the lines of my paternal grandmother, Bonny Jean. She was an intellectual, a fiery Christian Scientist, and natural skeptic who believed in God but not doctors, grassroots journalism, and stockpiling mayonnaise in case there was another Great Depression.

She grew up behind the stage with her parents, who were traveling actors. I once attempted to explain “gay people” to her because, you know, as a relic she wouldn’t understand such things. She spun around to face me in her house robe and said, “I grew up behind a vaudeville stage in the twenties. You think any of those people were straight?” I never tried that shit again.

She had five children from 1945 to 1955. They were raised largely by her father-in-law while she ran her newspaper, which she and my grandfather purchased in 1956. Bonny Jean would attend every local city council meeting, critiquing what she saw in scathing weekly editorials, which she would often dictate over the pay phone in the city council hallway. She once fought the head of the San Francisco plumbers’ union, a man with rumored Mafia ties, who was trying to take over her small town’s water council. When she broke the story and refused to back down, he threatened her. I once asked how she managed to fight a man like him as a woman in the 1960s. She said, “Oh, that was easy, honey. I was not afraid of him. The truth is a strong defense.”

When I told her about the pregnancy, I thought I heard a touch of sadness in her voice, despite her congratulations, because for a split second, they sounded like condolences.

The hardest person to tell was my father. I was barely old enough to handle him knowing I had sex, and yet I had to tell him there was an actual human growing in my body, deposited there by the sperm of a man. Telling him felt something like bra shopping with my mother at fourteen: uncomfortable in a deeply shameful, yet unknown way. Everybody has sex. Everybody gets boobs.

Still, somebody please kill me.

I had always felt my father saw me as a kid who was going to do something impressive in life, who was going to become a lawyer or doctor or at least make a lot of money. Instead, I was joining the Mormons in the kitchen. I knew he wouldn’t say it, but he would be disappointed in me. He knew how many times I had stood at family functions declaring my plan, and he knew I never consciously abandoned that.

It’s hardest to fall in front of those you’ve convinced, through years of tone moderation and personality suppression, that you are not the type to falter.

I stopped smoking and drinking immediately after my balcony denial, which felt wholesome and deeply mature, despite Mac’s and my decision to move out of our apartment and into his parents’ house on their ranch. They lived in a dome-shaped house about ten miles outside of Davis, California, the clean, well-manicured town where I went to college and met Mac.

Davis boasts the second-highest per capita number of PhDs in any city in the nation, and a special tunnel for frogs so they don’t get killed on the road. The town is teeming with students, artists, and intellectuals on bicycles, but also suffers from an epidemic of highly educated, splendid liberals. I learned to spot and avoid the latter from a distance of approximately one hundred feet, having had many years’ practice. The problem is not that they’re liberal—surely one can learn to live with that—it’s that they can’t quite understand why a person wouldn’t dress her child in only organic cotton, or shop solely at the co-op, where they sell nineteen dollar olive oil pressed from olives grown on blessed trees in sacred Native American valleys.

These are the kind of people who call gentrification “restoring the neighborhood” and spend four years on a waiting list for a $1,500 a month preschool while claiming to deeply understand the plight of the underprivileged. Davis is the kind of town where everyone breathes social justice via diversity stickers on their Priuses, but many citizens request that the kids from the Mexican enclaves surrounding the town simply stay in their schools. It’s not about race. It’s just…you know…let’s talk about public radio. Do you support it? It’s kind of my cause. That, and the ACLU.

Most of the mothers in Davis were married, in their late thirties, and living in $700,000 houses when I showed up at age twenty-one, unmarried and pregnant. When I realized nobody would talk to me at the park, having dismissed me immediately as some sort of teen-pregnancy situation, Mac and I bought a pink diaper bag with a giant rhinestone Playboy bunny on the front. It was my subtle “fuck you” to everyone who wouldn’t talk to me anyway, and it almost convinced me I didn’t care.

I turned twenty-two that March and finished my last semester of college in September of 2001, two months before our baby was due. Mac worked at his father’s slaughterhouse on the ranch, and our bedroom was where Mac had played with Hot Wheels and G.I. Joes as a boy, and hid his weed at fifteen. We shared the home with five other people: his parents, two sisters, and his sister’s boyfriend. All the bedrooms were upstairs and opened into a shared center hallway, kind of like Foucault’s panopticon only without the glass. His family was kind and relaxed and pretended we weren’t kids about to have a kid, but I felt exposed and watched—too close to people who weren’t quite mine, humans I knew but didn’t understand, and whom I was still trying to impress. They were family, but I didn’t want them to see me naked, or notice I stunk up the bathroom or yelled at their son. I self-regulated, even though there was no guard in the watchtower.

We bought a crib and an oak dresser, which we wedged together in a corner of the bedroom. I lined each drawer in lavender-scented paper with tiny pastel pink flowers on it, and I bought clothes from Baby Gap and Gymboree and Marshalls. I bought most of them in “newborn” size because they were the cutest and least expensive. I didn’t know they were discounted because babies outgrow them in twelve minutes.

We had a keg of beer at our baby shower, and Mac came because we were “too in love to be apart.” I received about seventy-five various bath items because when my stepmother asked, “What do you need for the baby?” I answered, “Bath items.” I didn’t know you were supposed to “register.” I didn’t have any friends telling me about pregnancy or babies because only losers had babies this young. And I never hung out with losers.

My pregnancy was like living in a dream, a sort of ethereal fantasy ticking by in nebulous form. While my belly grew, I spent my days petting hand-smocked outfits with embroidered ducks and imagining our little threesome. Mac and I played pool at my local university’s student union, and I wasn’t even embarrassed of my belly. I wasn’t embarrassed of my age, or Mac’s lack of career, or that we lived in a room in his parents’ house. Those things weren’t in the dream.

But I couldn’t help but feel inklings of shame as I walked to class during that last semester, when I barely fit in the desks, because the sidewalks and grass and offices on campus were the places where women like me rarely succeeded, and nobody was impressed with expanding uteri. These were PhDs and MAs and lovers of Derrida. They could see right through me: I was the kid who lost, the girl who failed. As I walked I remembered maybe I was going to be more than this, but then I thought of Mac and the baby girl to come. I thought of that love and squared my shoulders.

We went to peaceful birthing classes and breathed together and when Ava came it was fast and insane and Mac sat by me and held my hands and never broke my gaze. The nurses said we were the most beautiful birthing couple they had ever seen.

I wasn’t surprised. It was the only way it could be.

I met Mac for the first time in my living room the night before Halloween, thirteen months before Ava was born. I was living in a converted garage in a house I shared with four eighteen- and nineteen-year-old males I had found in a newspaper. Three months before I responded to their “roommate wanted” ad, I returned home from a year studying abroad in Spain. I tried living with my mother up north in Mendocino, California, and found a job waitressing, but got fired after two weeks for counseling the owner on how she could improve her business. I found myself bored, embarrassed, and broke, so I moved back to Davis in the fall and began waitressing at an “Asian fusion” restaurant and drinking too much.

I had long before decided I could not live with women. They were too complicated. They needed things like talking and support and genuineness. I needed things like rum and Coke and silence. So I asked those boys looking for a roommate if I could move in, and they said yes immediately upon hearing I could legally buy alcohol.

Three months later, a man I had never seen before sat stoned against our living room wall, next to the television. He had a beard that stuck out in every direction and a head of hair that looked exactly the same. It was as if somebody had taken a donut of three-inch-long black curly hair and popped a face into the center of it. He was a high school friend of my roommates’, a newcomer, thin and tall and quiet, and I would not have noticed him at all had he not said something witty. In our house of drunk eighteen- and nineteen-year-old man-boys, nobody was saying anything witty. I beamed my eyes at him from across the room in curious surprise and locked them with his. They were the kindest eyes I had ever seen. I remember that moment exactly as it happened, in slow motion, as if it were a scene in a Meg Ryan movie. The Eye Lock. His were deep brown with eyelashes that carried on ridiculously, but it was their gentleness, their steady calm, that made me want to know more.

brushed and your lipstick on straight. But you end up giving into pleas for the new Barbie, don’t even know which is the fancy wine, and never seem to leave enough time to brush your hair before the guests arrive.

brushed and your lipstick on straight. But you end up giving into pleas for the new Barbie, don’t even know which is the fancy wine, and never seem to leave enough time to brush your hair before the guests arrive.